Like any totally-normal-not-at-all-obsessed person, I spend a lot of time thinking about automatons.

Mostly, I shake my fist at the sky like an old man complaining that kids these days only like their sleek, human-passing, electric robots and no one cares about the wind, fire, water, and clockwork powered beings that preceded them. Is MonkBot not sexy? With that sweet, sweet segmented mouth action?

Automatons are usually thought of as no different from golems, living dolls, or patchwork girls. Just another category of animated being: nifty, sure, but so what? But automatons are, and have always been, important. And for two thousand years we knew that.

In the arc of human invention, automatons predate paper. That means before we thought “sure would be nice to write things in a convenient and portable manner” we thought “sure would be nice to have an inhuman creation in our shape that moves.” Then we immediately looked at this thing we’d made and instead of believing we’d become gods, we thought we’d created them. In ancient Rome and Egypt, as well as during the medieval period, automatons were representations of the divine. Even after they shifted into the realm of entertainment, automatons were singular wonders, art that brought joy to the viewer.

If you’re interested in getting a peek at how these fascinating machines used to be viewed in society, and what changed, below are three stories you absolutely must read…and one you absolutely must not.

The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2007) by Brian Selznick

(Honorable mention to the film Hugo (2011) by Martin Scorsese)

This wonderfully illustrated novel tells the story of a boy who has spent two years alone, tending to the clocks of a train station and attempting to fix a broken automaton. Once he discovers the key to making it work, the repaired automaton begins to draw a clue to its origins. This novel is great because it blurs the lines of machine and man. It is Hugo who mechanically tends to the clocks at the same designated time each day, Hugo who has no one to care for him. He is more like an automaton than a boy, and his reentry into the world of other people makes it feel less like the title is referring to an invention owned by Hugo, and more like it refers to his being invented as a person again after spending years as a machine.

The reason you should read this novel is not just to learn that the line between human and automaton is blurry at best, but to see how actual automatons once functioned. Hugo’s care for his machine echoes the way these intricate machines would have been treated by their creators. Never mass produced, never expected to fill the traditional labor roles we associate with robots like Rosie from The Jetsons or even Siri today, but amusements for the sake of it, a meeting of science and art. Most importantly, the automaton in Hugo Cabret and the story of its discovery are REAL… almost. In 1928 a mysterious box of parts was given to Philadelphia’s Franklin institute where workers reassembled the machine with largely no idea what it would be when they were done. Once they finished repairing the mechanical boy—officially named “Maillardet’s Automaton”—they discovered he could draw. Unlike the automaton in the novel, this one replicates four drawings and three poems in two languages. Also, this automaton was actually made in the year 1800, over a hundred years before its recreation in Philadelphia, which makes it one hundred years older than its literary counterpart in the book.

“The Pretended” (2000) by Darryl A. Smith

“The Pretended” takes place in a world where all black people have been killed by a white supremacist society and replaced with fabricated beings whose speech and appearance are caricatures of blackness. We learn that this annihilation was deemed necessary because those in power wanted to pretend black people weren’t people, which was harder to do while they were alive. The plan backfires, because even these new creations exhibit personhood, and must also be destroyed.

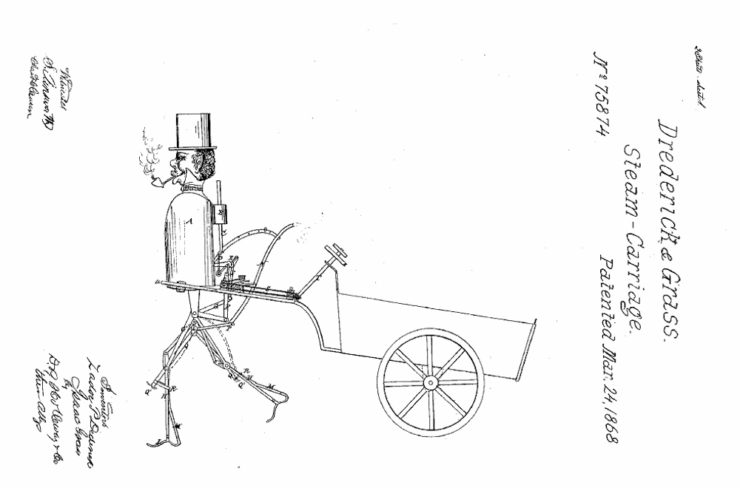

This story exemplifies the hardest aspect of automatons for people to grasp—as evidenced by the squinchy faces I get when I explain that I work in both posthumanism and critical race theory—that even beings that were never “born” can be racialized. Not only can they be, but automatons in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century were so often orientalist depictions that one reader writing into New York’s Christian Register in 1844 complained: “Why are all automata dressed in turbans?” When the first “American” automaton—Zadoc P. Dederick and Isaac Grass’ Steam Man—is designed immediately after the Civil War, its patent illustration takes the form most strongly associated with labor in the mind of Americans: a black man.

On one side of this 1868 automaton is two thousand years of wonder and the delicate, handmade, boy-machine writing poetry and drawing ships from Hugo Cabret, on the other is the assembly line and Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), forever wedding automation and labor in both reality and fiction.

“The Sandman” (1816) by E.T.A. Hoffmann

“The Sandman” is your standard “boy meets girl, boy falls in love with girl, boy never notices that girl doesn’t communicate, boy sees girl disassembled and the sight of eyes sitting on a table drives boy mad” tale. You know, classic. But what makes this one so interesting is over two hundred years ago Hoffman resisted the urge to paint the male protagonist, Nathaniel, as a purely duped victim and instead leaves him with, “Bruh…she never communicated and you were cool with it?”

The last section details the effect the story of the female automaton had on the men who heard it: “Many lovers, to be quite convinced that they were not enamoured of wooden dolls, would request their mistresses to sing and dance…and, above all, not merely to listen, but also sometimes to talk, in such a manner as presupposed actual thought and feeling…”

Hoffman even gives the final insult to OG sadboi Nathaniel by having Clara, the fiancée he was stepping out on with the automaton, move on happily: “she at last found a quiet domestic happiness suitable to her serene and cheerful nature, a happiness which the morbid Nathaniel would never have given her.”

Hoffman uses the figure of the automaton here to show us that they are wonders of science and works of art… but if that is all you’re looking for in a partner you might be one set of disembodied eyes away from jumping off a cliff.

L’Ève future (Tomorrow’s Eve) (1886) by Some Jerk…

…just kidding, his name was Jean-Marie-Mathias-Philippe-Auguste, Comte de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam (Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam for short) which, in my defense, does roughly translate to “Some Jerk” depending on where you put the accent.

Buy the Book

The Space Between Worlds

In this novel a distressed lord comes to his inventor friend, none other than Edison himself, with a problem: he’s found a girl who’s wicked hot, but he doesn’t like her mind. She’s either too virtuous—as in, she didn’t want to keep her virginity for the right reasons—or not virtuous enough—as in, she is fallen, but not in a way he can appreciate. She’s too practical. She’s not too stupid, but rather not stupid enough (“A woman who has lost all her stupidity, can she be anything but a monster?”). The solution? Make a copy of her body and replace the brain with a more palatable version. Literally render her body as an object separate from her personality for the purpose of sexual possession. The novel holds that Alicia herself is not exceptional in her unworthiness, but that women in general are a problem. In one scene the inventor pulls out a drawer full of wigs, corsets, pantyhose, makeup, birth control, etc. and declares the contents of the drawer is everything that makes women. Might as well turn them into sexbots, after all, it’s what they do to themselves.

I am not saying you shouldn’t read this novel because there is nothing it can teach you about the legacy of the automaton. I’m saying you shouldn’t read this novel because it can teach you, and sometimes you can be taught things that are wrong. With this novel, Villiers ignores and erases the lesson laid down by E.T.A. Hoffman exactly seventy years earlier. Why strive to hear your beloved’s voice, he tells men of the time, when you can just replace it with one that pleases you?

By remembering automatons we remember how the prioritization of art can become bulldozed by wants of industry, the miraculous giving way to the profitable. These creations are still essential to study, because when humans create in their own image they also create a tangible snapshot of the values and visions of the world at that moment. Sometimes, that image is of religious devotion. Sometimes, it’s an image of intellectual curiosity and wonder. But sometimes they are darker, cautionary tales exposing how power operates against the powerless.

Micaiah Johnson was raised in California’s Mojave Desert surrounded by trees named Joshua and women who told stories. She received her bachelor of arts in creative writing from the University of California, Riverside, and her master of fine arts in fiction from Rutgers University–Camden. She now studies American literature at Vanderbilt University, where she focuses on critical race theory and automatons.